"See one, do one, teach one.” This adage, credited to Dr. William Stewart Halstead (1852-1922), emanates from the origins of the modern program for surgical training. Halstead, dubbed the father of American surgery, emphasized the importance of mentorship.

The adage means that a trainee must first observe the technique of surgery, then perform and perfect the skill, and, finally, as a surgeon, pass on that skill to a younger colleague through apprenticeship.

Mentorship holds a central place in surgery, because unlike other disciplines of medicine, the trainee surgeon needs to learn practical technical skills that may not be easily acquired by studying the written literature alone. Mentoring in surgery is so important that, according to research, up to three-quarters of surgical trainees have been found to choose the same specializations as their mentors.

In the college-without-faculty that is Toastmasters, mentorship and peer feedback are the only “teachers” we have.

I know this issue well, because I, too, benefited from mentors when I was a surgical trainee in Kenya. From these established surgeons, I learned several lessons and “survival tips” that I keep up today.

The first one is to be confident that whatever I do will be supported by my seniors as long as it is backed up by scientific evidence and intended to alleviate a patient’s suffering.

Second, I seek comfort in the face of difficult surgeries by doing my best. There is a comfort that comes with knowing you did your best, but your best should not be equated to trying to create a brand-new limb for a patient who is horribly injured. It gives you the moral energy to proceed to serve the next patient.

Third, I carry the mantra “be complicated in your thinking but simplistic in your approach.” It helps with reflecting on “what is the worst that can happen?” or “what if your choice of surgery does not work?” It is a memorable line from one of my mentors, a pediatric surgeon.

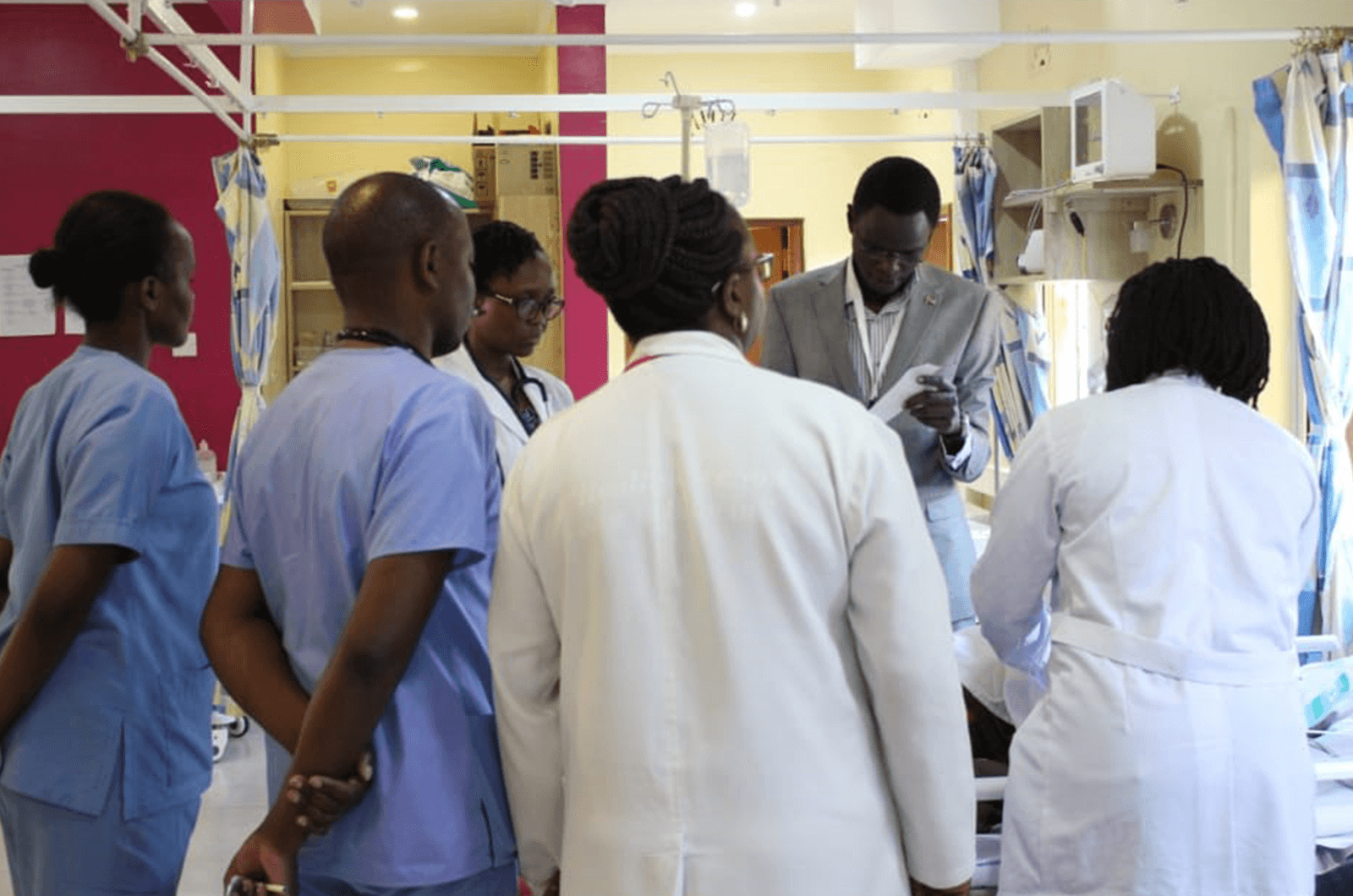

Dr. Aruyaru, director of medical services, consults with staff members at St. Theresa Mission Hospital in Meru, Kenya.

Dr. Aruyaru, director of medical services, consults with staff members at St. Theresa Mission Hospital in Meru, Kenya.Today I am the director of medical services at St. Theresa Mission Hospital in Meru, Kenya. Yet every time I get into a difficult operation, I always ask myself, How would my mentor have approached this?

After I joined the Kilele Toastmasters Club in Nyeri, Kenya, and took on a few speaking and meeting roles, I was quick to notice certain parallels between Toastmasters’ education program and surgical training across the world. The Toastmasters program centers on four pillars: experiential learning, self-paced learning, peer feedback, and mentoring. These tenets are also at the heart of surgical training. As my club’s Vice President Education, I have seen firsthand how a member can rapidly grow in their learning experience when they make use of a mentor. In the college-without-faculty that is Toastmasters, mentorship and peer feedback are the only “teachers” we have.

How Does the Mentor Benefit?

The benefits of being a mentee are obvious for all to see. But how does the mentor grow? How does a mentor benefit after helping the mentee? When you teach others, you learn as well. I have found this true in Toastmasters’ Pathways learning experience. For example, after completing a Pathways project, I found that I benefited more when I mentored a member on the same project.

When I finished my Pathways Level 5 project “Advanced Mentoring,” I delivered a speech to my club in which I highlighted my four main mentoring strategies. I called them the ABCD’s of being a successful mentor:

Agree.

As a mentor, it is easy to imagine you know best what your mentee needs. I harbored such thoughts until I sat down with my mentee to set the goals. “Stanley, I am not in Toastmasters to be an orator. I am here to learn as much on leadership as possible.”

This statement by my mentee, a member of my club, was an awakening. It helped me taper my expectations into the objective ones we agreed on. It is similarly easy for mentors in surgical training to assume they know everything their trainee needs. More and more surgical training programs are itemizing what the trainee needs before the cycle of a formal mentoring engagement.

The first step is to agree on the expectations of the mentee and the objectives that need to be met.

Be a good example for your mentee.

Be a good example for your mentee. As I highlighted before, nearly three-quarters of surgical trainees end up picking the specialization of their mentors. They feel inspired when they see a surgeon who is a master at their craft. In a young club like mine, where there are no seasoned or Distinguished Toastmasters to emulate, a mentor can inspire their mentee through leading by example. I once discussed with my mentee the need for him to use the stage more effectively and minimize the use of notes during speeches. When I took a speaking role the following week, I knew I needed to practice what I preached. I made sure not to carry any notes to the lectern. The pressure was suddenly on me because of my mentee’s expectations.

Cede control.

The fast-paced mentor might want to push the mentee to complete their projects early or have their draft speeches ready a week before the meeting. This approach would change the dynamic from mentoring to coaching. As a mentor, I felt this was tempting. Luckily for me, the mentee did not change. He still gave his draft to me four days before the meeting, and he delivered on the areas we had discussed. It was a learning experience for me: I realized that the pace and direction of the mentorship should be dictated by the mentee.

Ceding control of the relationship to the mentee not only empowers them, it makes the mentoring relationship comfortable and enjoyable. We learn best in moments of enjoyment, as Toastmasters founder Dr. Ralph Smedley once observed.

Do not chase after time.

Dr. Job Mogire, a former Toastmaster in Wichita, Kansas, and author of the book Born to Win, argues that “if you are building something worthy, time is your friend.” (Think of the picturesque Great Pyramid of Giza taking 20 years to construct.) As a mentor, I learned patience. I sometimes worked with my mentee on certain areas of improvement for speech delivery. I then sat and watched them deliver the speech and felt that those areas were not executed as rehearsed.

By the third project, however, I started noticing changes and improvement. This is the essence of Toastmasters education—it is self-paced, to give the member time for quality and growth. In surgical training we do not just confine a trainee to a university hospital for five years and get them out. The competence-based curriculum ensures that this time is filled with continued and repeated exposure to learning and performing surgeries at increasing levels of competence and complexity. It is okay to sacrifice rapid results at the altar of continual general improvement.

There is great similarity between the strategies applied by mentors in Toastmasters and mentors in surgical education. While the mentee is the obvious intended beneficiary in a mentoring relationship, the mentor stands to retain much of what the mentee learns if they apply such education in the form of teaching or peer mentoring.

The ABCD strategies, which include agreeing on the objectives from the start, setting a good example for the mentee, letting the mentee control the speed and direction of the relationship, and being patient, will result in a great experience for both the mentee and the mentor.

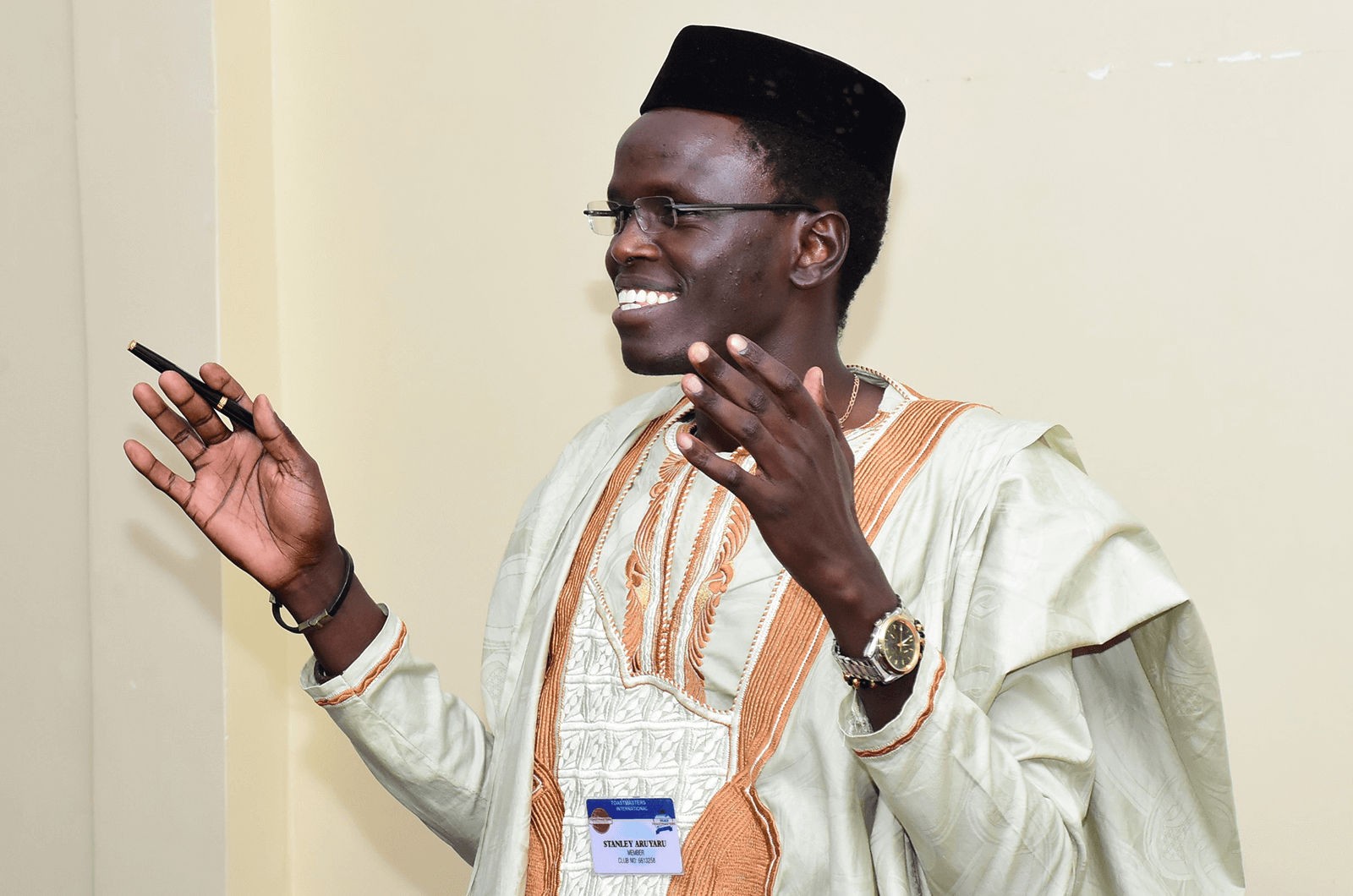

Dr. Stanley Aruyaru a member of the Kilele Toastmasters Club in Nyeri, Kenya, is a consultant general surgeon and the director of medical services at St. Theresa Mission Hospital in Meru, Kenya. He is also the associate editor of the Annals of African Surgery—the peer-reviewed official journal of the Surgical Society of Kenya.

Previous

Previous

Previous Article

Previous Article