Click play to hear an exclusive podcast interview with the author, Kristen Hamling, and the hosts of The Toastmasters Podcast.

Last year I gave a virtual speech about workplace resilience to business leaders during lockdown in New Zealand. I desperately wanted to make a good impression and persuade my audience to take mental health more seriously.

Up until just before the speech, I was calm, confident, and self-assured. My confidence came from years of attending Toastmasters, completing a Ph.D., and my work as a trauma psychologist.

But my experience accounted for nothing the moment I felt pressured to be the best, which is what I felt when I started to speak. My creativity and spark were replaced by anxiety and fear. I felt sick and light-headed and couldn’t remember part of my speech. I had put so much pressure on myself that my body reacted as though this speech was a life-or-death situation, and my performance suffered as a result.

The Science Behind the Fear

I am not alone in my experience, as Toastmasters well know. Matt Abrahams, a lecturer on strategic communications at Stanford University in California, says “Communication anxiety is absolutely normal.” Wanting to make a good impression when we speak publicly is natural and helps us maintain status within our group. Historically, increased status in a group kept you attached to your tribe, which promoted survival. Public speaking threatens our status in the group because we become singled out and open to scrutiny, says Anwesha Banerjee, DTM, Ph.D., a neuroscientist and member of Dogwood Club in Atlanta, Georgia.

Banerjee explains that when we feel vulnerable, the primitive parts of our brain get activated to coordinate the body’s survival response to danger, which primarily is fear. In her TEDx Talk “Stage Fright: Don’t Get Over It, Get Used to It,” Banerjee says that, as far as the body is concerned, public speaking is akin to being stared down by a tiger.

As a trauma psychologist, I’m all too familiar with the fear response. In my practice I consistently observe anxiety and fear stopping people from performing at their best and achieving their goals. I’ve had a few clients whose fear of public speaking is so intense that it’s considered a phobia. As a result of fear and physical symptoms of stress, they either avoid all forms of public speaking or endure it with significant distress. This true phobia of public speaking is called glossophobia, which is sometimes linked with a traumatic event in the person’s life. If you experience this level of fear, you may want to seek professional help. For those of us whose symptoms are unpleasant but not debilitating, the following advice could help. And Toastmasters is the perfect place to practice.

Connection Trumps Perfection

Lesley Stephenson, DTM, a professional speaker and Toastmaster in Zug, Switzerland, teaches people how to manage their fear of public speaking. She says, “Stage fright is normal; live with it.” She recommends to stop trying to fight the symptoms of stage fright and instead learn how to manage them. “Public speaking gets easier and better over time as fear gets replaced by a lovely sort of buzz of excitement.”

Stephenson says preparation is the key to reduced speech anxiety. She recommends writing out the entire speech, but to memorize just the beginning and ending. Trust your rehearsal and knowledge of the material to deliver about 70% of the script. Stephenson says, “When you try to remember your speech word for word, it reduces the conversational tone, which in turn increases disconnection with the audience.” Instead, she suggests to aim for “connection over perfection,” noting that social connection activates our body’s calming response and reduces anxiety.

Letting go of perfectionism is an effective way to manage fear of public speaking. Banerjee, a native of India, focuses on developing a relationship with her audience rather than appearing perfect. Although she has an accent and says she makes grammatical errors, she recognizes that she receives far more positive feedback for being genuine and authentic than she does for being a “perfect” speaker. Banerjee embraces the idea that “it’s perfectly okay to be imperfect.”

The Window of Tolerance

Effective preparation was something my virtual speech lacked. I didn’t get enough sleep the night before and I was unfamiliar with giving online speeches. I should have practiced more. It also took place at the beginning of the pandemic and my stress levels were high. The lack of planning resulted in too much stress, which pushed me outside of my “window of tolerance.” That is the optimal zone of arousal where you perform most effectively.

“Public speaking gets easier and better over time as fear gets replaced by a lovely sort of buzz of excitement.”

–Lesley Stephenson, DTMToo much stress activates your sympathetic nervous system (the “fight, flight, freeze” response), which takes you outside your window of tolerance. When outside your window, your attention becomes preoccupied with the negative. You may focus on the slightest of mistakes or interpret others’ behavior in a negative way. Like when we think that one person’s yawning is evidence that our speech is terribly boring. We lose sight of the possibility that the yawner may not have slept well the night before, and we can’t refocus our attention on the 50 other interested faces in the audience.

The other thing I try to remember when speaking in public is that you can’t please everyone. I think of my audience as a bell-shaped curve: Some people will love your speech, some people will think it’s okay, and some may even hate it. Stephenson’s advice is to “remember that people are really quite fickle, so don’t aim for popularity; aim for respect.”

Although moderate public speaking jitters can promote performance, too much anxiety can prevent meaningful connections with your audience. Abrahams explains, “Nervousness can make your audience very uncomfortable.” If your audience notices your nervousness, he says they can’t concentrate on the message and instead worry about your ability to deliver it. So how do you dial down the anxiety to a manageable level?

Emotional Regulation

One of the best ways to manage anxiety is through mindfulness. It brings you into the present moment so you can observe your thoughts and feelings without reacting to them. For example, had I practiced mindfulness during my speech, I would have noticed that my thoughts (e.g., I have to deliver the perfect speech or people will think I’m incompetent) had become catastrophic and irrational. Mindfulness would have allowed me to notice my thoughts, let them go, and focus on doing my best.

This quality can be achieved in many ways, but a good start is with mindful breathing. Bring your attention to your breath and the feeling of it entering your body. Follow the breath for 10 minutes. Slow diaphragm breathing activates our parasympathetic nervous system—the body’s calming response. Other mindful activities include naming three things you can see, feel, hear, and touch, and focusing on what you are grateful for in the moment. Try a mindfulness exercise whenever you find yourself worrying or imagining the worst-case scenario.

Having the ability to manage strong emotions is critical for public speaking. Sometimes anxiety is a good thing, as it gives you the energy to take on a difficult speech, says Abrahams, the Stanford lecturer, but other emotions, like shame, could ruin a speech if not carefully managed. Abrahams makes a good case for emotional regulation in his 2018 TEDx Talk, “Speaking Up Without Freaking Out.” He explains how he successfully navigated shame during a speech that saw him split the backside of his pants in a failed karate kick.

Ethan Kross, a professor of psychology at the University of Michigan, found that when people talk to themselves in the third person (e.g., how should Kristen get ready for her next speech?), they gain psychological distance from their problems. Kross reasons that when a friend comes to you with a problem, it’s relatively easy for you to coach them through it, because you are psychologically distant from the problem. Your friend’s problem doesn’t seem as urgent to you. Perhaps the simple trick of psychologically preparing in the third person might help you to better prepare for and deliver your next speech.

Habituate Your Fear

Creating new speaking habits is also an effective way to stop yourself from overthinking during a speech. Banerjee, the neuroscientist at Emory University in Atlanta, Georgia, says that completing a task for the first time requires a lot of thinking, and overthinking can generate anxiety and lead to inner strife.

As a psychologist, I often see this happen. A client of mine recently became acutely nervous about making a speech and her thoughts began spiraling. She said, “If I do badly in my speech, then people will talk about me behind my back. I’ll get bullied and be all alone; then I’ll get sad and depressed.” Our brain can come up with all sorts of scary scenarios when we’re stressed, and our body reacts as if each of those thoughts may come true. However, when a repeated action consistently leads to a good outcome, our brain encodes the process, which creates a new habit. If you form enough good habits in public speaking, you can habituate your stage fright, says Banerjee.

We can create new habits by following the three-step process of cue-routine-reward, which was put forth by Charles Duhigg, author of The Power of Habit. I tried this technique with a client whose stage fright made him lose his voice during a first performance. Afterward, we created a new cue for his upcoming shows: Holding an amethyst crystal during the performance would remind my client to stay calm and present. We then practiced a new routine: Pause, breathe, touch the crystal, and say, “You’ve got this.” At the second show, he nailed it, providing the reward for his cue and routine. By the third and fourth shows, my client had formed new habits and reported having some fun with his performance.

“It's perfectly okay to be imperfect.”

–Anwesha Banerjee, DTM, Ph.D.Although facing any fear can be scary, the growth and resilience we develop along the way are worth it. Banerjee reports that the increased self-confidence she’s gained in public speaking enables her to speak up in situations that she would never have in the past. She can confidently hold a conversation in any context, and as a result, her personal and professional network has grown. But facing your fear of public speaking requires effort. Hopefully, the advice in this article is more reliable than my father’s advice to me: “Just imagine everyone in the audience is naked.” Luckily, I joined Toastmasters, and everyone gets to keep their clothes on.

For more support and information about the fear of public speaking, check out Toastmasters International’s webinar series: Lose the Fear, Learn the Relevance.

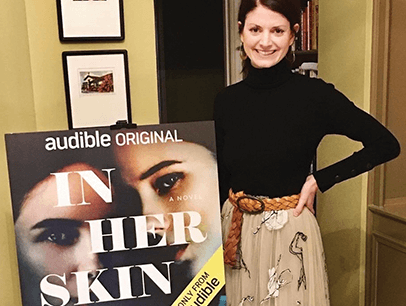

Kristen Hamling, PhD is a trauma and positive psychologist and a Toastmaster in Whanganui, New Zealand. She is the founder of Wellbeing Aotearoa, which focuses on trauma-informed well-being practices. A facilitator, coach, and researcher, she has also served in the Australian Army Reserve. Learn more on her website.

Make Those Nerves Work for You

Make Those Nerves Work for You